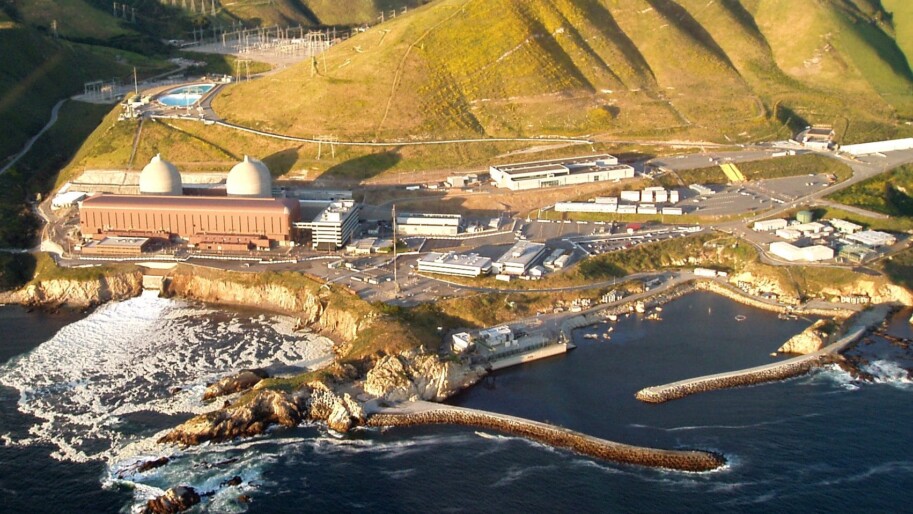

On January 11, the California Public Utilities Commission voted unanimously to close down the Diablo Canyon nuclear generating station in San Luis Obispo by 2025. Diablo is the last operational commercial nuclear power plant in California, so when it closes, California will have closed its chapter of nuclear power as an energy source. California is often a leader on a wide variety of things, so let’s hope the rest of the world eventually follows California on this one. It is the right decision, not just for California, but for the world.

California law forbids building more nuclear plants in the state until the federal government creates a long-term solution for dealing with the radioactive waste they produce. But nuclear waste is far from being the only problem with nuclear fission power. Nuclear power imposes a web of hazard on the world. The problems begin with the extraction of uranium with all kinds of negative impacts to workers, communities, and the environment. Then there is the risky transport of radioactive material, and as we have learned more than once, hazards exist at operating nuclear facilities. Then there is the connection between enrichment of uranium for power generation and also for weapons of mass destruction.

In 2013 I learned in a chance encounter with a PG&E engineer, his first-hand account about a few other hazards that we don’t often hear about – and the costs associated with them.

The encounter was with someone I will call the Diablo Songbird (DS). Don’t want to get anyone in trouble. I was on my annual camping trip in Yosemite with my wife and brother-in-law. We were sitting in our camp one morning discussing Sonoma Clean Power, which was at that time still in the formation process. We were talking energy. After about 20 minutes the camper in the next site ambled over and said that he couldn’t help overhearing a bit of our conversation, that he found it interesting, and could he join us. We invited him to pull up a chair.

It soon became clear from his comments and questions that he knew more than a little bit about energy. I asked him if he worked in the energy sector. “Yes I do,” he said. “Oh, well what do you do?,” I asked. “I work for PG&E,” he said. “Really!, and what do you do for PG&E?” “I work at the Diablo nuclear plant.” “Oh really!” I said, “and what do you do at the plant?” “I am a senior engineer in the control room.” My cowboy coffee almost went through my nose.

The relaxed Yosemite environment, random nature of the encounter, and distance from the real world added up to DS feeling safe to not only talk, but to vent a bit about his concerns.

June 2013 was only a little over two years since the Fukushima disaster, and DS and his fellow engineers were still engaged in an intense period of analyzing what happened there, and comparing that incident to their own situation on a cliff above the waves on the opposite side of the Pacific. DS said they were “freaked out” by what happened in Japan, and freaked out by what they were learning in the early stages of a seismic review that had been ordered by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

He said that although there were some significant differences between the two sites, Diablo being much higher up above sea level for example, there were enough similarities that there is good reason to be concerned.

Then DS shifted his comments to a set of realities driven not by Fukushima, but by an event ten years earlier – 9/11. What DS conveyed made it clear that you can throw any claim of nuclear power being “low cost” out the window. He said that ever since 9/11, millions upon millions of dollars have been spent, off the books, at Diablo alone, maintaining a 24/7 no-fly-zone with staffed anti-aircraft artillery, a no-float-zone in the ocean for a broad radius around the thermal outflow of the plant, and 24/7 on-site military personnel guarding the facility in ways unrelated to the no-fly and no-float zones. DS went even further by fretting aloud that just like they can never fully vet their own civilian personnel for mental stability, there is no way to ever be 100% sure about the military personnel, and he alluded to instances where unstable people were discovered. Scary stuff.

Toward the end of the conversation, DS described another recent development that had him and his fellow engineers in the control room nervous. This time it was something that relates directly to the recently stated reasons for closing the plant. He explained that the higher-ups at PG&E had conveyed to them a request from the California Independent System Operator, asking them to report back regarding whether or not they would be able to ramp power up and down, as opposed to maintaining the baseload power at a constant hum, as nuclear power plants are designed to do.

The reason for this request was, of course, the recognition on the part of the grid operators that the variability of wind and solar power, and the new dynamic nature of power flow on the grid, makes large, rigid, inflexible chunks of power on the grid far less useful or valuable. The question alone was enough to make an engineer jittery. Thermal fluctuations are the last thing you want affecting integrity the concrete and steel of a nuke plant and that’s precisely what you get when you try to increase or decrease power output. Although they were still in the phase of evaluating the request, DS assured us that they were planning to respond with essentially a rejection of the notion. Diablo was designed to start up and just keep running.

Back to the recent past…

In June 2016 PG&E introduced a Joint Proposal to retire the Diablo by 2025. The Joint Proposal included provisions to replace Diablo power with efficiency, new renewables, and storage. Expenses associated with the replacement energy would be billed as “non-bypassable charges,” which means that the costs would have to be paid by all customers who purchase electricity supply directly from PG&E. However, other customers —including Community Choice customers— who do not actually get their electricity from PG&E would also have to pay under the proposal simply because their electricity is delivered over PG&E’s wires.

In response the Center commissioned a study, “Clean Energy Replacement for California’s Nuclear Power Plants,” to assess the degree to which replacement power was even needed for Diablo. One of the paper’s findings is that the PG&E claim that retiring Diablo will seriously damage California’s climate policies is invalid, because the State’s various clean energy policies rapidly replace, and over time far exceed, the amount of electricity provided by the nuclear plant. Community Choice Energy is playing prominent role in exceeding the state minimums.

The bottom line about nuclear fission power is that it is an extremely expensive and exceedingly perilous way to boil water. Now the power that was once hailed as being too cheap to meter cannot be generated profitably according to Anthony Earley, former CEO of PG&E, and that’s leaving those off-the-books anti-terrorism expenses out of the calculation.