-

Our aging and unstable electrical system must be replaced now, not decades from now

This piece was originally published in the Mercury News opinion section on October 25, 2019. (Subscription required.)

The dramatic increase in the size and severity of California’s wildfires in recent years is just one example of the devastating effects of climate change. PG&E’s power shutdowns this month due to high-fire-risk wind conditions is a stark reminder that our aging and unstable electrical system must be replaced now, not decades from now.

In response to power shutoffs, homeowners, businesses and managers of critical facilities, such as city halls, fire stations, hospitals and schools, currently buy fossil fuel-powered back-up generators. But dirty diesel generators are not the solution. They are heavy polluters, noisy, expensive to operate and are themselves a fire risk. Further, replenishing the supply of diesel fuel is not always possible during an emergency.

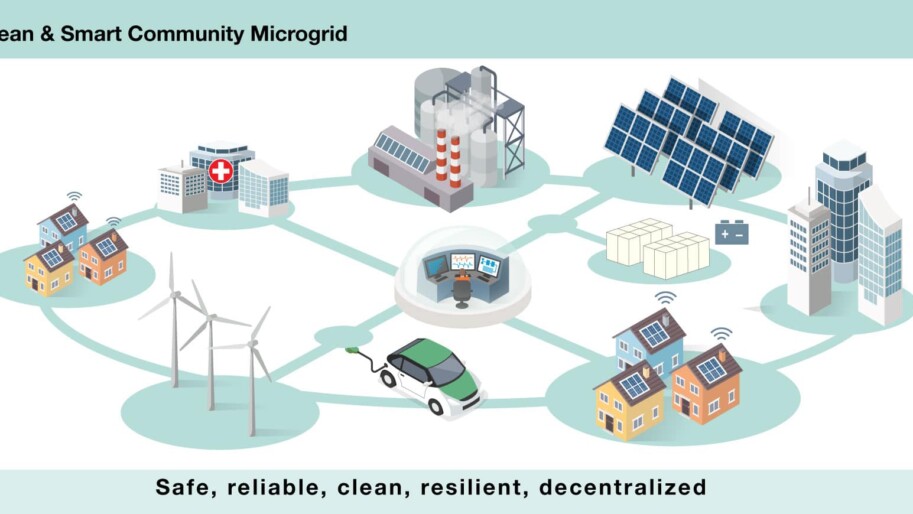

There is a better way. California needs a new decentralized power system with clean, resilient energy sources. A more resilient system would reduce the number of outages both planned and unplanned. A decentralized system would enable utilities to better target specific outages and operationally isolate local electricity generation from the larger grid. This would ensure that essential governmental, health and other services would remain powered in communities during outages.

To get started building a decentralized system from the bottom up, every community should identify its critical facilities—water supply, wastewater treatment, first responders and community care centers—and decide where to install new local renewables and storage to create community microgrids. Building microgrids at the community level to generate and store electricity makes more sense than leaving it to random business and residential deployments with everyone prioritizing their own facilities and needs.

To accelerate building community microgrids, The Climate Center started the Advanced Community Energy (ACE) initiative. ACE works to provide funding, technical expertise and local capacity for cities and counties to plan and implement local clean energy and battery storage systems to keep the lights on when grid power goes off. ACE planning involves collaboration between local governments and stakeholders, from residents including those in disadvantaged neighborhoods to electric distribution utilities, clean energy developers and technology companies.

Some California local governments have already started developing community microgrids, such as in Oakland, Eureka and Santa Barbara. These efforts need to expand to other communities soon. A statewide program to ensure that all cities and counties have the funding and technical support to conduct collaborative, participatory planning processes is essential.

To fully implement community microgrids statewide, we must transform our regulatory policies and institutions by revising market rules so that thousands of small-scale-distributed energy resources can be compensated for providing local energy services. We need to direct the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to develop regulatory rules for the big electric utilities to collaborate in good faith with the cities, counties and other stakeholders in their service areas.

We also need market signals to enable this transformation, starting with increased state funding to support critical facility microgrid projects. The first state supported community microgrids should be established in high fire risk areas in disadvantaged communities, and eventually should cover all of California.

Community microgrids are the logical next step in California’s remarkable history of energy policy innovation. The Advanced Community Energy initiative offers a blueprint for engaging local governments and the communities they serve in creating a clean, resilient, more affordable and equitable electricity system.

Ellie Cohen is CEO of The Climate Center, a California-based nonprofit working to enact the bold policies required by the science and climate reality to reverse the climate crisis.

Many thanks to Kurt Johnson, Susan Thomas and others at The Climate Center for assistance in writing this piece.