You don’t have to be a climate nerd to appreciate a good carbon footprint map.

Measuring carbon emissions is a little like counting calories and steps. Just as data collection has emerged as a winning tool for achieving better, life-saving health (think FitBit), so too can data inform species-saving strategies for the health of the planet. Whether we’re talking about obesity or climate change, the outcome, if not dealt with swiftly and sustainably, is indubitably grim.

Chris Jones is the lead developer of the nation’s most comprehensive inventory of consumption-based greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The Climate Center had the pleasure of welcoming him to Sonoma County on March 17 to share his research with the Regional Climate Protection Agency and later at a public event co-hosted by the Leadership Institute for Ecology and the Economy and The Climate Center.

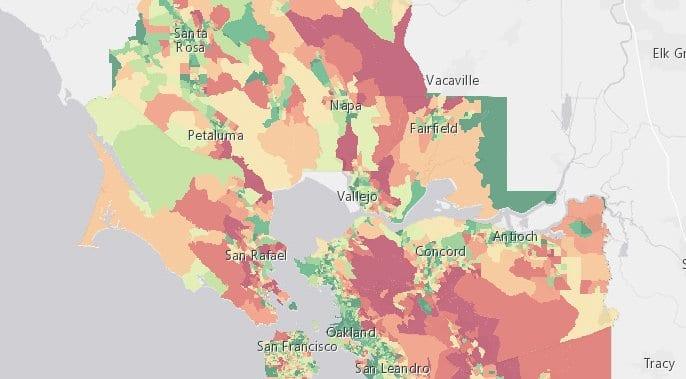

Chris and colleagues at UC Berkeley have produced the first comprehensive consumption-based inventory of greenhouse gas emissions, providing data down to the zip code across the country, and now to the neighborhood scale (census block groups) in the San Francisco Bay Area. Consumption-based emission data are calculated by physical units of consumption from transportation, energy, and food, as well as per dollar expenditure on goods and service. Emissions are expressed in metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e) per household and in total per location, including all cities and counties in the Bay Area.

This type of carbon accounting differs from the production-based accounting that we typically see. A production-based assessment doesn’t factor in many of our indirect and imported emissions, especially from the food, goods and services we consume. Chris’s team finds that the consumption-based inventory of the Bay Area is about 35 percent larger than the region’s traditional production-based inventory. The consumption-based approach more accurately reflects the distinctions between the carbon footprints of urban and rural, and affluent and low-income communities.

Although the map displays quite a lot of green, we have much work ahead of us. Green may indicate “good,” but good isn’t good enough for future generations. The positive news is that within this consumption-based inventory of greenhouse gas emissions resides many opportunities to identify unique local and regional solutions to the climate problem.

Some important take-aways from the data include:

1. United States consumption habits generate significant carbon emissions. In fact, it would take an 80% reduction in our emissions to reach the global average, according to Chris, and another 80% to get to the climate stabilizing level we need to be. 2. Transportation is the biggest carbon culprit. The average household in California generates most of its emissions – more than 18 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year (mtCO2/year) – from transportation. Just over half of that (about 9.5 mtCO2/year) is from the gasoline we pour into our vehicles. Food is the second largest source of emissions, responsible for almost 9 mtco2/year of emissions. About two-thirds of California’s food footprint comes from meat and snack foods. Housing is the third largest contributor to emissions.

2. Transportation is the biggest carbon culprit. The average household in California generates most of its emissions – more than 18 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year (mtCO2/year) – from transportation. Just over half of that (about 9.5 mtCO2/year) is from the gasoline we pour into our vehicles. Food is the second largest source of emissions, responsible for almost 9 mtco2/year of emissions. About two-thirds of California’s food footprint comes from meat and snack foods. Housing is the third largest contributor to emissions.

3. California’s emissions are about 4 mtCO2/year less than the national average, mainly due to our mild climate and cleaner electricity. Nationally, the average housing footprint (including electricity, gas, other fuels, water, waste and construction) is 13.4 mtco2/year vs. 7.2 mtco2/year in California. In the Bay Area, the housing footprint shrinks further, to 5.8 mtco2/year, with only 1 metric ton from electricity.

4. Big cities have the lowest emissions. However, the urban sprawl surrounding those cities counteracts the positive benefits of dense urban centers.

5. 92% of GHG emission variability across the country is a product of 6 determinants: vehicle ownership, income, household size, size of home, carbon intensity of electricity, and population density.

Putting the Data to Work

The research of Chris and his team can inform climate planning at a regional and local scale to identify the most effective strategies to reduce emissions.

When cities and counties look at their emissions patterns over time, they can prioritize solutions through policy decisions. With California’s population estimated to grow about 30% by 2050, we need as many solutions as possible to dramatically reduce our carbon footprints: education, individual behavior change, smart urban planning (such as meeting and exceeding SB 375 commitments), efficiency and conservation, and new technology.

Technological advances, namely in the energy sector, show the most promise for reducing emissions at the scale needed. “While electricity is a very small part of the problem, it’s a huge part of the solution,” Chris said. In fact, he said that electricity is “the biggest part of the solution. We need to electrify our vehicles, our heating, and our economy. And it all needs to come from clean, renewable energy.”

Another important way to significantly reduce our footprint is to address our high-carbon food sector. Chris said that this solution can be particularly impactful in urbanized areas where transportation emissions and other sources are already pretty low. “For health and food security reasons, it’s also really good to focus on food,” he added.

Under the consumption-based greenhouse gas inventory, food turns out to be a much bigger source of emissions, accounting for 20% of overall household footprint, versus just 2% in a production-based inventory.

Chris and the researchers at CoolClimate Network have recently completed an inventory for every city in the California, with policy scenarios that project greenhouse gas emissions reductions through the year 2050. The data are not yet released, but we got a preview and it was illuminating. If we can successfully implement the tools at our disposal, climate stabilization is possible.

You can’t manage what you don’t measure. Chris’ research is a powerful tool to help us measure the causes and quantities of emissions we consume so that we can design a manageable carbon diet.

—

About Chris: Chris Jones is Program Director of the CoolClimate Network, a research program of the Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley. He also serves as Program Chair of the Behavior, Energy and Climate Change Conference. His primary research interests are carbon footprint analysis, community-scale greenhouse gas mitigation, environmental psychology, and environmental policy.

About Chris: Chris Jones is Program Director of the CoolClimate Network, a research program of the Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley. He also serves as Program Chair of the Behavior, Energy and Climate Change Conference. His primary research interests are carbon footprint analysis, community-scale greenhouse gas mitigation, environmental psychology, and environmental policy.

About the study: The results and interactive carbon footprint map are available at http://coolclimate.berkeley.edu/inventory. This work was funded by the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD) in preparation for its forthcoming Regional Climate Protection Strategy.